Rediscovering Gems

Written by Amelia Kedge, International Training Programme Assistant

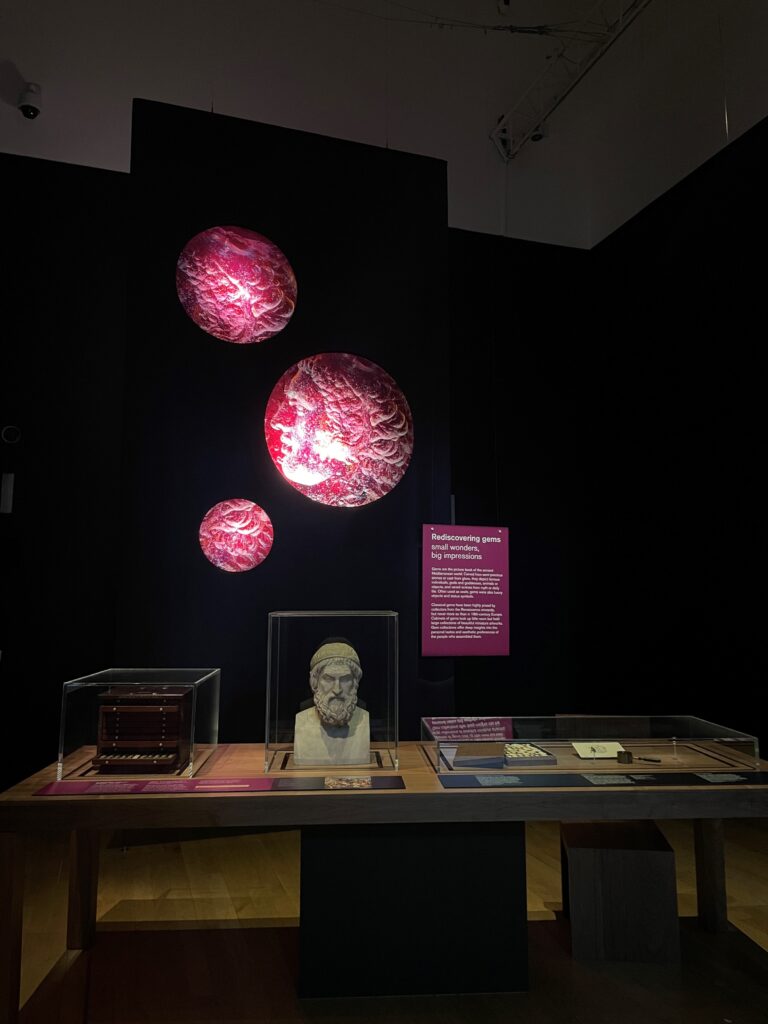

Currently on display in Room 3 here at the British Museum are a collection of classical gems from the Romans to the Renaissance. Depicting deities, animals, and scenes from myth and everyday life, these small artworks are highly sought after by collectors, and controversially forged by fraudsters.

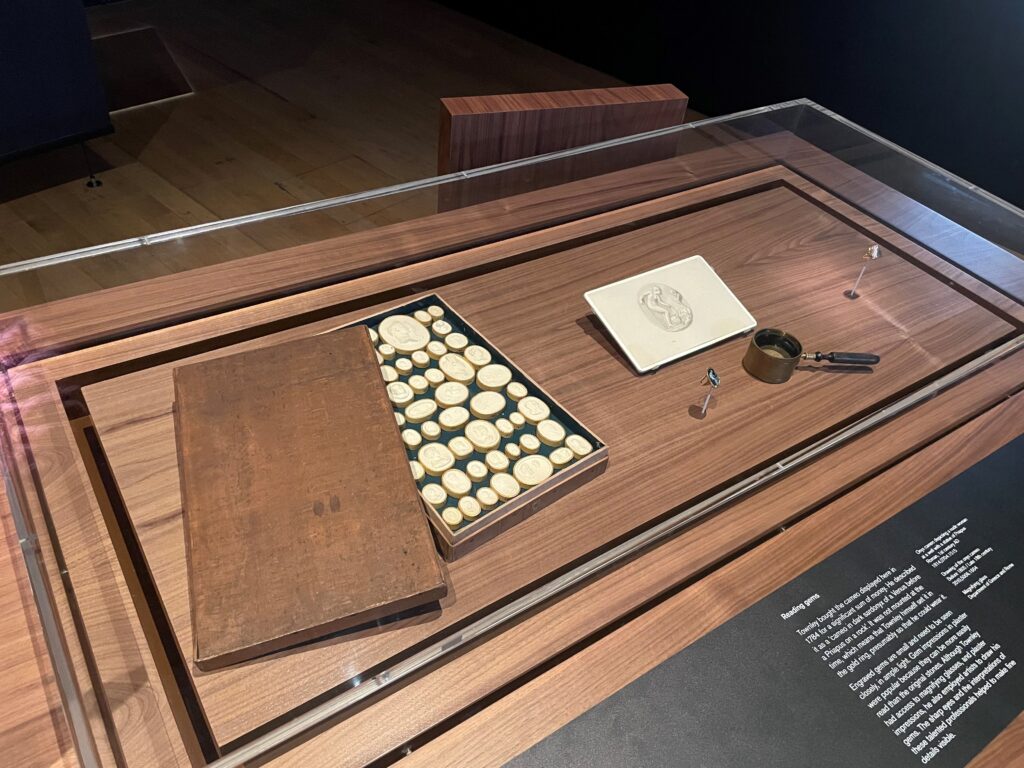

Carved from semi-precious stones or cast in glass, these gems were luxury objects and status symbols for those who owned them. The 18th century was a highpoint for interest in engraved gems, with antiquarians such as Charles Townley (1737 – 1805) boasting vast collections. Townley displayed his collection in specially designed cabinets with handwritten notes documenting the objects’ provenance.

As classical gems were held in such high regard, wax and plaster impressions were commercially produced for scholars and connoisseurs to study. Their increasing accessibility encouraged engravers to copy famous examples and create new intaglios in the style of the best ancient artists. Gem impressions from Italian engraver Tommaso Cades are displayed here in boxes resembling books.

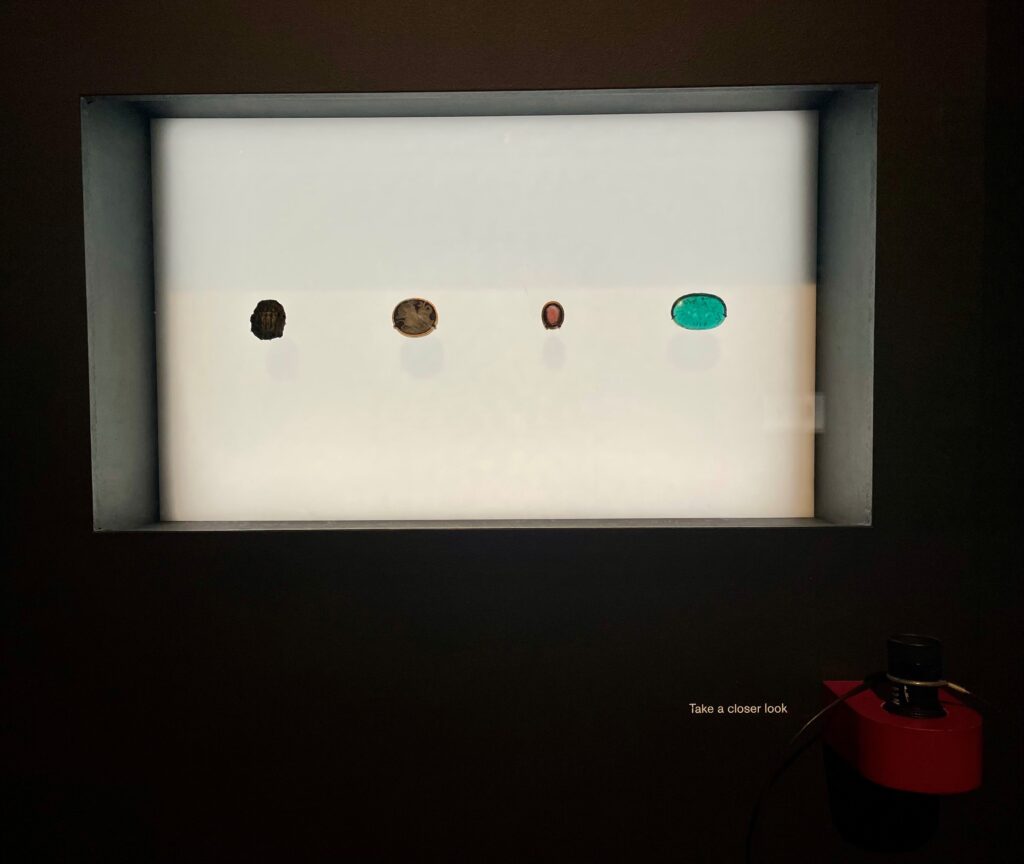

Cameos, gems where the design has been carved in relief, were popular in the 1st century with religious subjects and imperial portraiture and were worn as jewellery pieces. The Blacas Cameo is a beautiful example of this, depicting the emperor Augustus in layered sardonyx stone. The minute detail is incredible, with Augustus wearing a headband embellished with its own tiny cameos and precious stones.

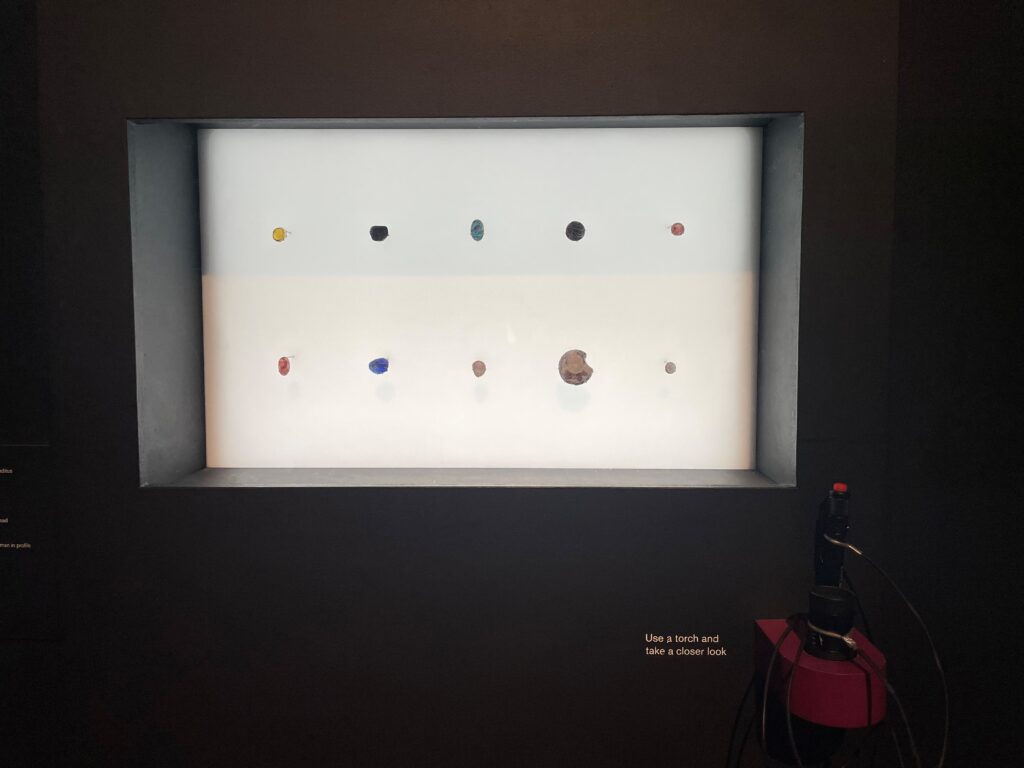

Glass gems were typically engraved in semi-precious stones like quartz. In the later 1st century Roman workshops started manufacturing glass gems that imitated hardstone. This was a difficult process where glass was pressed into a mould and the excess removed before being mounted. Many were unfinished or never set in a mount, such as the cameo depicting the Three Graces (far left in the image below).

Glass and stone gems were copied and imitated in the modern period, and sometimes deceitfully sold as ancient. These fakes flooded the market in the 19th century, finding their way into many collections. This explains why generations of scholars dismissed this class of object. Today, scientific analysis can successfully detect and date fakes by identifying additives in the glass.

This case displayed 10 gems are among hundreds recovered recently by the British Museum following the discovery that many were missing. Most of these gems had been poorly documented. Some are clearly modern, like the glass cameo with the bust of a bearded man. Several are genuine multi-coloured glass gems, or ‘wasters’ discarded in antiquity in the course of production.

Addressing the recent thefts from the collection, the final exhibition panel read,

In August 2023 the Museum announced that a number of items had been stolen, were missing or damaged. It became apparent that the collection of engraved gems had been targeted, including the Townley and Blacas collections. Everyone at the British Museum is committed to recovering all the stolen items, and to preventing thefts from happening again.

A dedicated team within the Museum is working tirelessly with the Metropolitan Police Service, and with an international group of experts in gems, collection history and art loss recovery, to retrieve the missing items. This work is challenging because many of the missing objects have never been fully documented. As a result, the Museum is embarking upon a major project to catalogue and photograph the entire collection, and to make this information freely available online for everyone.

Please visit the British Museum’s website for the latest information about the recovery programme.

www.britishmuseum.org/our-work/departments/recovery-missing-items

For me, the exhibition sheds light on these tiny treasures and the fascination they have inspired for centuries. It was interesting to learn how highly prized they were, despite their size, and the lengths to which they were forged and faked. It was also good to see the work the museum has been doing to recover the stolen artefacts, and to see them on display once again.

Rediscovering Gems is on display in Room 3 at the British Museum until 2nd June 2024.